Provence – with its’ Roman ruins, medieval villages, and quiet layers of illusive history – has inspired visitors for decades. It beckons to a France much different than its’ northern counterparts. Even the culinary offerings differ vastly. While the diet in northern France is cream and butter based, the Provençale diet is far more Mediterranean – rich in olive oils and vegetables. Northern France, for its’ centuries of royal courts, wars, and intrigues, has vast resources of available historical archives. Today’s southern France is a kaleidoscope of diverse and fragmented regional histories, many buried in the stones with unwritten legacies. In fact, large parts of Provence were not even a part of France until after the French Revolution in 1791.

Here is a brief glimpse through time, nations and the balance of power over the centuries that has shaped Provence as it exists today.

Table of Contents

The Greeks and the Romans

While prehistoric evidence in southern France dates as far back as 400,000 BC; the ancient Greeks settled in Marseille (known as Massalia) in 600 BC.

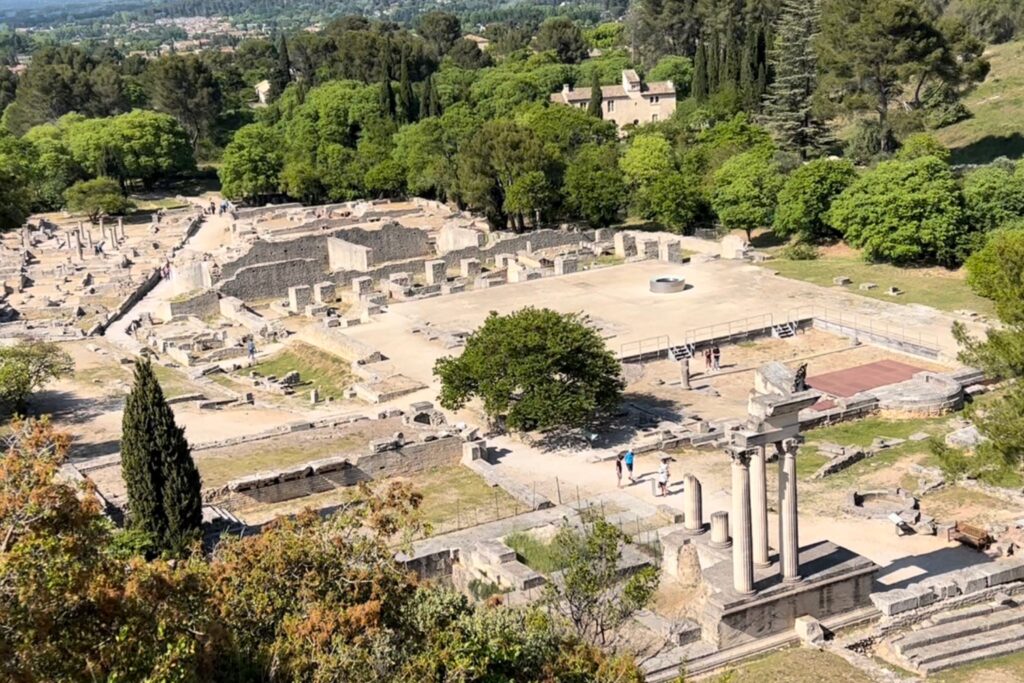

The area just north of Marseille was settled by the Celto-Ligurian tribe known as the Salyens during the 4th to 2nd centuries BC. They built a fortified town, Glanum, around a spring known for its healing powers. A shrine was built at the spring to the Celtic god – Glanus. When wars ensued with the Greeks of Marseille, the Greeks called upon Roman allies to help them fight the Salyens. In 125 and 124 BC the Salyens were defeated by the Romans and many monuments were destroyed. The town rebuilt their monuments, which were destroyed again in 90 BC in another rebellion against the Romans. By 49 BC Julius Caesar captured Marseille from the Greeks and the romanization of Provence and Glanum began. It became “Provinca Romana” – the first official province of Rome and is the origin of the area we know as “Provence.” Provence and the town of Glanum prospered under Roman expansion until 260 AD (over 300 years) until the Germanic tribe – the Alamanni – destroyed the town. Local residents abandoned Glanum and moved north, where they built the city that has become St-Remy-de-Provence.

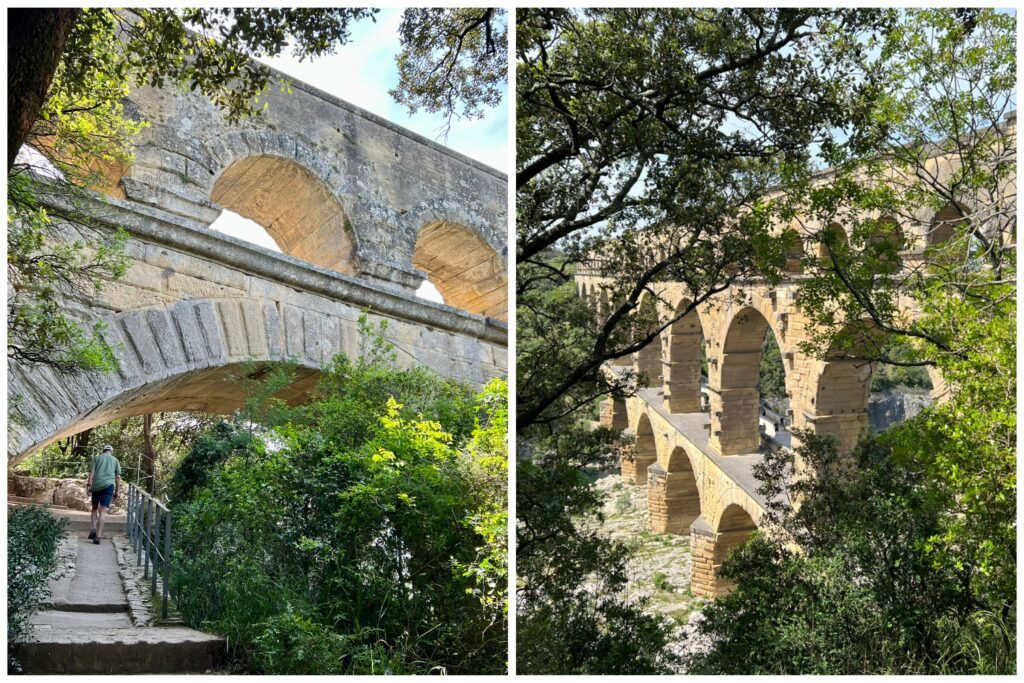

2,000 year old Roman structures are found throughout the south of France. A few of the well-known sites include Nimes, Arles, Orange, Vaison-la-Romaine, Aix-en-Provence, and of course the Pont du Gard aqueduct, which are still visited today.

Two thousand years ago the Romans built Pont du Gard, the highest aqueduct running 31 miles, to carry fresh water from the Fontaine d’Eure, located at the foot of Uzes, to the Roman city of Nemausus, now the city of Nimes. The waters of the spring came in part from the Alzon River, which passes through the vicinity of Uzes, and in part from the harvested waters of Mount Bouquet, located closer to Ales. The aqueduct itself is an amazing feat of engineering and a testimony to the mastery of ancient builders. The elevation difference between the starting and finishing point is only 12.6 meters, making the overall average slope only 24.8 cm per kilometer!

The Barbarians and the Franks

The fall of the Roman Empire in 476 AD was followed by several decades of feuding barbarian powers including the Visigoths, Burgundians and Ostrogoths. In 536 AD Provence fell under the Kingdom of the Franks. In 561 it was divided among two different Frankish kings, which meant continuous conflict internally as well as attack by Lombard and Saxon raiders. In the early 700s, both internal rebellions and Arab attacks saw vast destruction, violence and death. While the reign of Charlemagne over the Frankish kingdom (768-814) brought calm and order, the region was deeply impoverished with the prosperous Roman infrastructure now in complete decay.

After 100 years of struggles for power, Provence entered four centuries of rule by Counts or Marquises of Provence, who were, in practice, independent rulers in continuous intrigues and power struggles, and not part of the kingdom of France.

The Comtat Venaissin & L’Enclave des Papes

In 1274, Alphonse, Count of Poitiers bequeathed the lands of the Comtat Venaissin to the Holy See, and it became a separate state owned by the Pope. In 1309, Pope Clement V (from Bordeaux) moved the Roman Catholic Papacy to Avignon, now its own Comtat, and from 1309 to 1377 seven Popes reigned from Avignon. In 1317, Pope John XXII purchased the town of Valreas and surrounds, forming another Papal state called L’Enclave des Papes. From 1377 to 1423 the Western Schism between Rome and Avignon churches led to rival Popes in each city until the seat of the papacy finally returned to Rome in 1423. In general the 1300s were a dark time in Provence, with much of the population lost to the Black Death between 1348 and 1350. After the defeat of the French Army in the 100 Years War between England and France, many cities and towns in Provence built walls and towers to defend themselves against armies of former soldiers ravaging the countryside.

The ”Good King Rene”

In the 1400s there were a series of wars between the Kings of Aragon and the Counts of Provence. In 1423 the army of Alphonse V of Aragon captured Marseille, and in 1443 captured Naples, forcing its ruler, King Rene 1 of Naples to flee. He chose to settle in one of his remaining territories – Provence and the city of Aix-en-Provence. When the “Good King Rene of Provence” died in 1480, his title passed to his nephew, Charles du Maine. One year later, when Charles died, the title passed to Louis XI of France. In 1486 the territories of Provence were legally incorporated into the French royal domain, with the exception of the Comtat Venaissin, Avignon, and L’Enclave des Papes.

Wars of Religion

Once a part of France, Provence was swept into the wave of religious persecution. During the Wars of Religion between the Catholics and the Huguenots that were engulfing France, many people of all religions sought sanctuary in Avignon, the villages of the Comtat Venaissin and the L’Enclave des Papes, which were directly under the Pope. There was still violence as the heads of the armies, on both sides, would raise money for their troops by ransoming local villages. After success with French villages, they moved on to villages of the Comtat. Most villages paid the ransom, but if they resisted and failed many of the residents were slaughtered and villages were devastated.

Rural Provence

In the early 1600s the population of Provence was about 450,000. It was predominantly rural, devoted to raising wheat, wine and olives, with small industries for tanning, pottery, perfume making, ship and boat building as well as textiles and silk weaving.

The histories of northern and southern France weave separate, occasionally intersecting paths through the Provencal landscape. Southern uprisings again the authority of the Bourbon King in 1630-1631 and 1648-1652 brought new royal forts and dockyards to Marseille and Toulouse in efforts to control the unruly population. Despite the plague of 1720-1722 that killed 40,000 people in Marseille alone, by 1800 Marseille had population of 120,000 and was the third largest city in France.

The Vaucluse Department

The Vaucluse (including of the Comtat Venaissin, Avignon and L’Enclave des Papes) did not become part of France until 1791, after the French Revolution, when it was annexed by the First Republic. It was not formally ceded by the Pope until 1812. During the years of 1274 to 1791, as a completely separate Papal State, it was neither subject to the Counts of Provence nor the King of France. It was not subject to French laws, taxes or military drafts. It is in the villages of the Comtat in the 1570s that I first find my ancestors. The stories of the lives in the medieval villages of the Vaucluse and Provence are an elusive labyrinth of partial records, invisible graves and brief mentions in dusty archives.

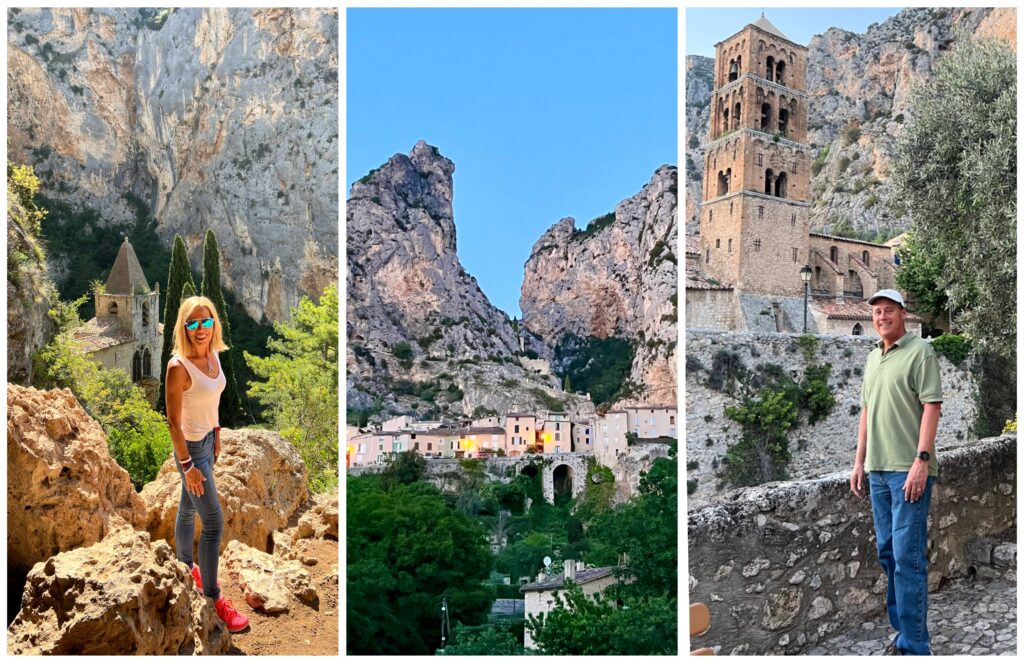

The Perched Villages of Provence

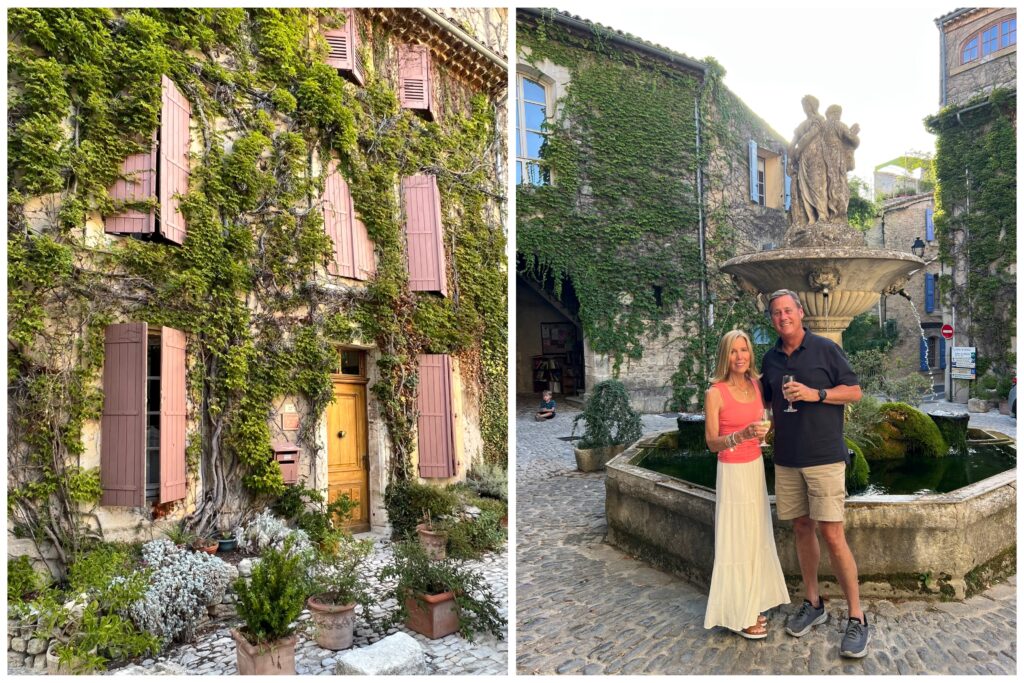

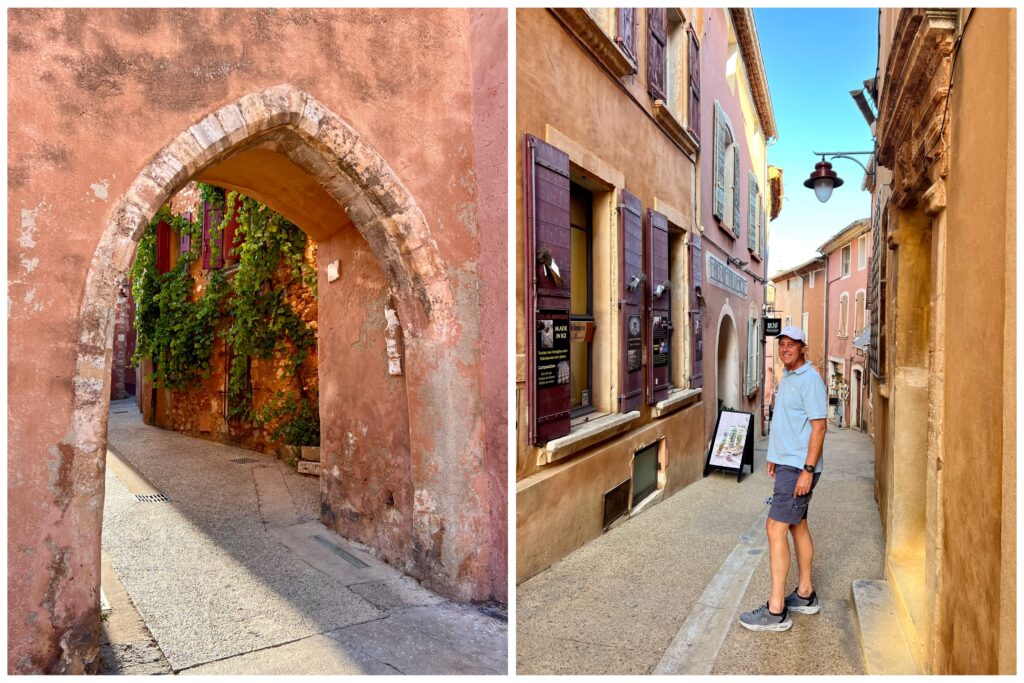

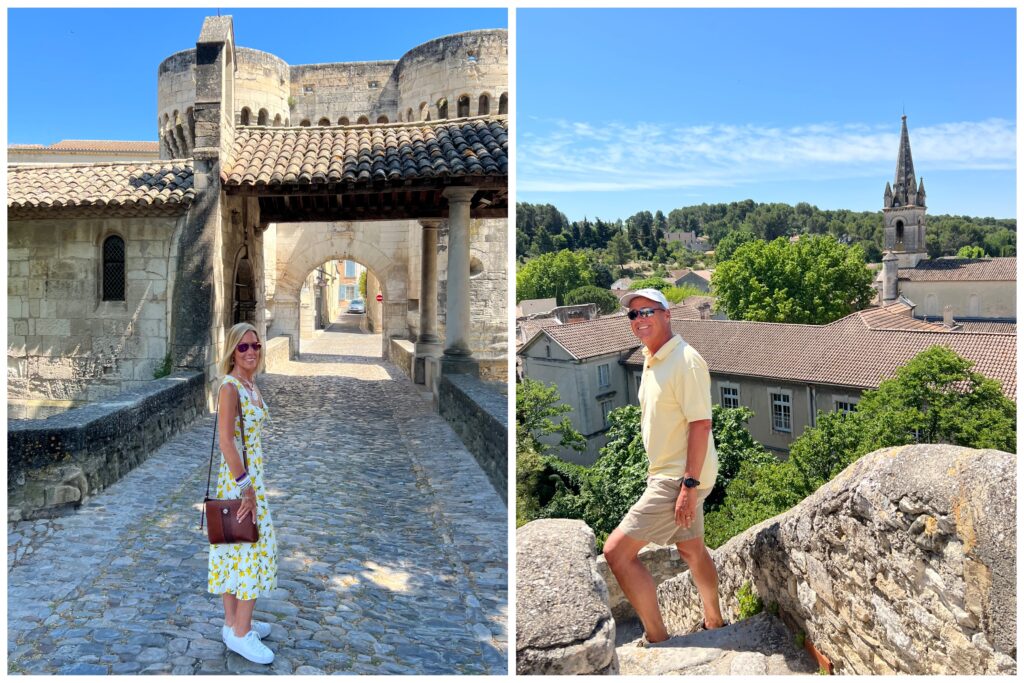

Endless hilltop, or “perched”, villages dot the landscape of Provence. Many were built around castles, with fortified walls that enclosed churches, belltowers and stone built houses. The fountains were vital sources of water for the village residents, and they all had at least one “lavoir” – a community laundry fountain – many that were still in use until the 1970s. These rocky promontories, high above the valleys, were much easier to defend against attackers. For most villagers, any travel would have had to be on foot, as few had the resources for their own cart, much less a horse or carriage. The great effort needed to travel – or even communicate with nearby villages – meant that they had to be self-sufficient. As trade increased, however, so did the challenges. In addition to being difficult to reach, the rocky hillsides had little access to water or fertile ground for farming or orchards. Slowly, villagers moved down the hills to local towns in the countryside. By the beginning of the 1800s, many perched villages started a decline that lasted well into the 1900s. In the later 1900s, as the relaxed belle vie of Provence grew popular with visitors, the life, light and color of these plus beaux villages re-emerged. Breathing new life into the ancient stone buildings, elegant hotels, warm bastides and village houses embraced a new wave of travelers. Delicious local restaurants, artisan shops and Provençale events throughout the region celebrate the past and the present. Today, wandering the beautifully manicured village squares and covered passages, the stones whisper of hidden histories and of people and times lost forever.

This is the first installment of the “Discovering Provence” series. Thank you for wandering Provence through time with us. Please let us know if you have any favorite historical discoveries in Provence!